TROPICAL SYNAPSES

Reflections on topics including clinical neurology, recent publications in neuroscience,

philosophy of biology, "neuro-doubt" about modern media hype of new neuro-scientific procedures and methods, consciousness, scuba diving, horticulture, jazz, blues, slack key guitar music, the Hawai'i health scene, and whatever else dat's da kine...

Transcranial alternating current stimulation improved working memory in the elderly

In 2012, the FDA decided to classify transcranial electrotherapy stimulators, which had been marketed for use in anxiety, depression, and substance abuse, as class 3 devices, requiring special permits for use, because of lack of efficacy. The FDA suggested that poor evidence for efficacy meant that use of the devices would take away from the use of better proven methods of treatment.

Yesterday, Nature Neuroscience published a study showing that alternating current transcranial stimulation increases working memory slightly in elderly adults who do not have dementia, but have a working memory deficit compared to younger adults.

How is the study device different from the alternating current stimulators that were developed 20 years ago and then reclassified as a failure 7 years ago?

One factor is certainly the location of the stimulation. The older devices had electrodes placed lower on the head, intending in theory to stimulate the thalamus. The new devices stimulate the frontal and anterior temporal areas.

Is the device clinically useful? That is not so clear. The military tested direct current cranial stimulators on its pilots about ten years ago and found they could shift skill sets in the pilots from styles favoring quick decisions to styles favoring slower but more accurate decisions. They were not able to successfully increase one type of skill without limiting another. More study will be needed to see if the new technique can help working memory without affecting other parts of cognition negatively.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

ABSTRACT

Article | Published: 08 April 2019

Working memory revived in older adults by synchronizing rhythmic brain circuits

Robert M. G. Reinhart & John A. Nguyen

Nature Neuroscience (2019)

Understanding normal brain aging and developing methods to maintain or improve cognition in older adults are major goals of fundamental and translational neuroscience. Here we show a core feature of cognitive decline—working-memory deficits—emerges from disconnected local and long-range circuits instantiated by theta–gamma phase–amplitude coupling in temporal cortex and theta phase synchronization across frontotemporal cortex. We developed a noninvasive stimulation procedure for modulating long-range theta interactions in adults aged 60–76 years. After 25 min of stimulation, frequency-tuned to individual brain network dynamics, we observed a preferential increase in neural synchronization patterns and the return of sender–receiver relationships of information flow within and between frontotemporal regions. The end result was rapid improvement in working-memory performance that outlasted a 50 min post-stimulation period. The results provide insight into the physiological foundations of age-related cognitive impairment and contribute to groundwork for future non-pharmacological interventions targeting aspects of cognitive decline.

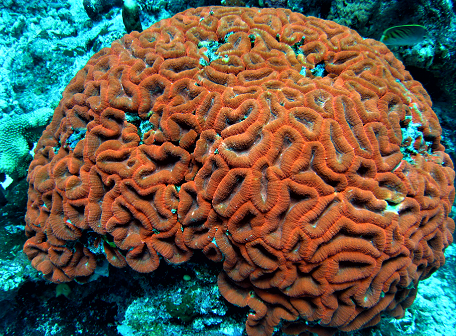

Cacao flower

Risks for impaired post-stroke cognitive function

In a printed posted to the medRxiv preprint archive this month, I found a chart review of patients with stroke to determine factors (other t...

-

According to the Nobel-prize-winning work in the 1960's by Sperry and Gazzaniga , after the two cerebral hemisphere are cut by callos...

-

The Ship of Theseus is a classic thought experiment in Greek philosophy. As related by Plutarch the historian, Theseus' ship was kept as...

-

Sanboukan sweet lemon citrus tree grafts after a month, unwrapped today. The first graft looks more solidly healed than the second. We wi...